Before booking a safari there’s a few things to be considered, from budget constraints to seasonality, what kind of wildlife you want to experience and if you’re preferring self drives or guided game drives or even walking safaris. There’s many factors that make a safari perfect and tailored towards your individual needs. But then there’s an essential criteria, that’s sometimes overlooked: The ethical aspects of going on safari.

In this guide we want to give you some insights into how to book an ethical safari – that truly benefits the wildlife, communities and ecosystems you visit.

The different aspects of ethical safaris

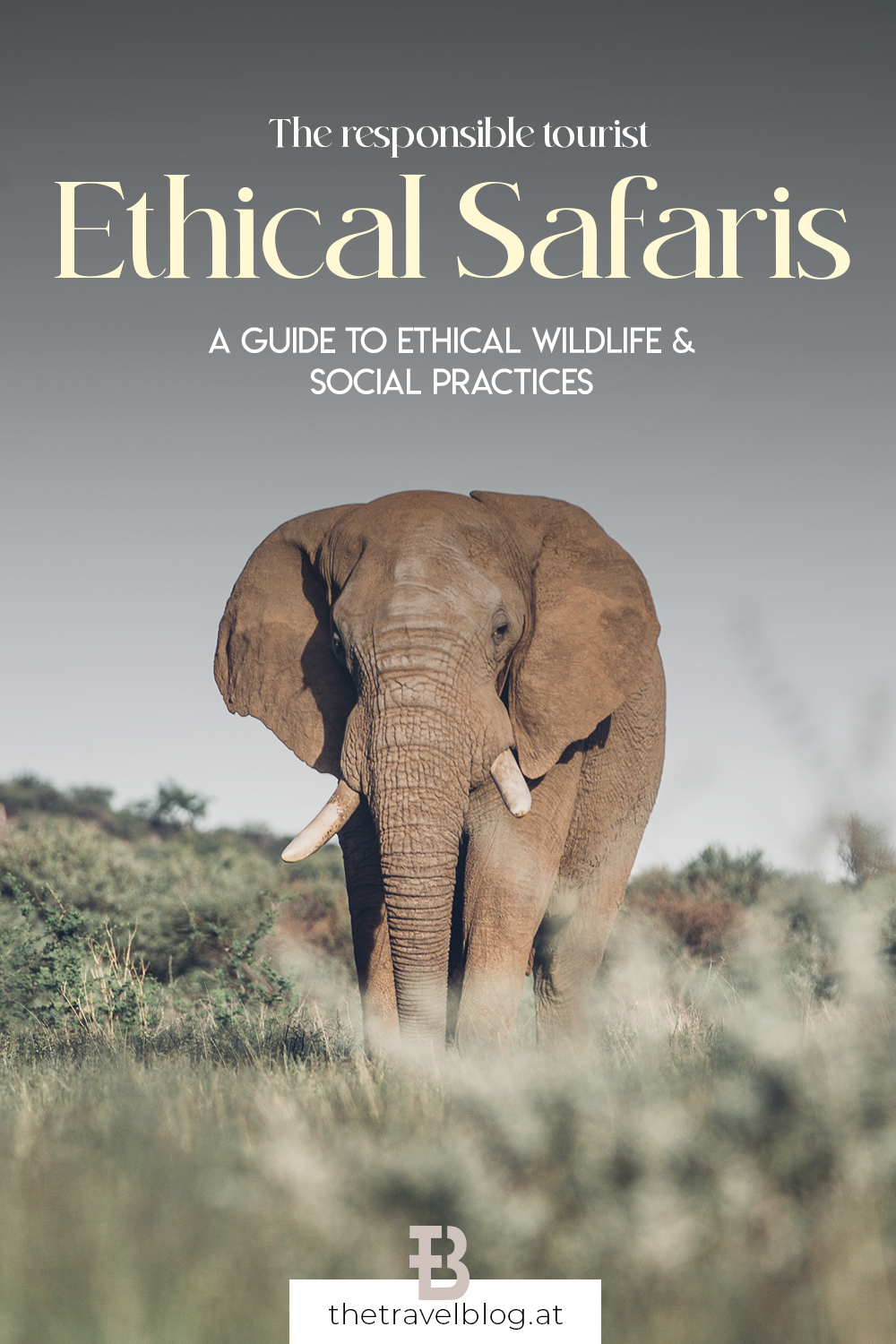

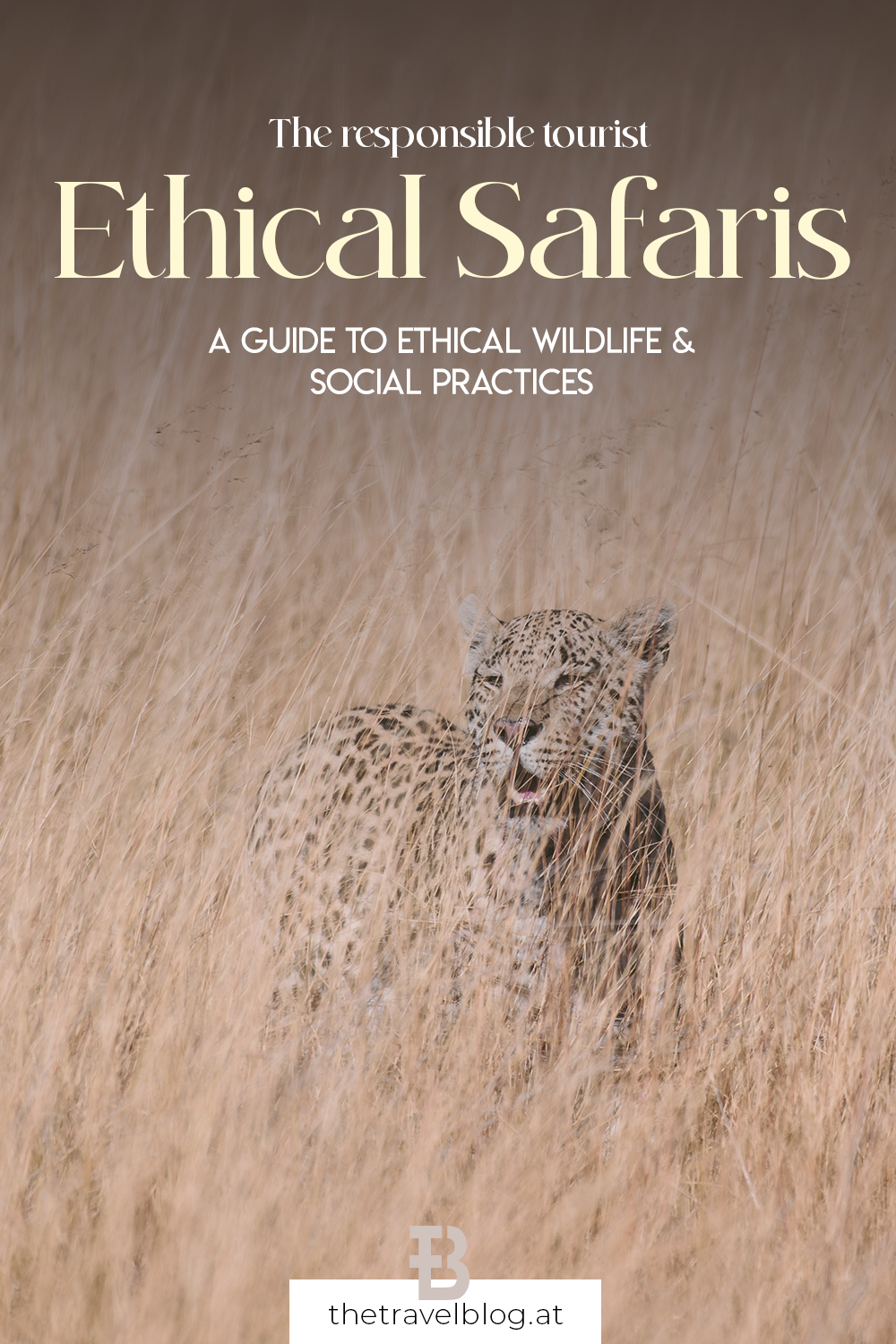

When it comes to ethics the first thing that comes to mind is the animal welfare. The wildlife you get to experience should thrive and actually benefit from the safari tourism. What sounds like a no-brainer is quite nuanced in practice.

The second element is the local impact you’re creating. Do residents of the regions you visit actually participate in the tourism industry actively and benefit from the revenues and are part of decision making processes?

And the third layer is the impact on the general ecosystems. With long haul flights bringing you in that’s already a considerable negative impact on the climate of our planet, but that is unavoidable for now. So the question is how you can minimise your local negative impact (think food production, waste management, local transfers, etc.).

- Ethical wildlife practices: How to protect the wildlife we cherish

- Ethical social practices: How to make sure people also benefit

- Ecological practices: How to protect the ecosystems we visit

Let’s look at each of those aspects in more detail.

1. Ethical wildlife practices

This is actually a wide-ranging topic and touches everything from policies (how wildlife areas are managed) to on the ground behaviour (giving wildlife space, no touching or feeding, etc.).

The policy part is actually the most complex, so we won’t be able to go into much detail here, but generally speaking you can assess how well managed a park or private concession is by factors such as transparency (yearly assessments of the wider ecosystem from biodiversity to numbers of specific wildlife, poaching incidents, local employment, etc.) and political stability (this impacts how area management contracts are set up, the more long-term management contracts are the better usually).

But let’s just say the policy part is quite complex and the more off-the-beaten-path you’ll go the more complicated it might get to assess the political situation. That doesn’t mean that things can’t get quite dirty in established parks (think corruption in parts of South Africa which leads to rising numbers in rhino poaching). So yeah, it’s complicated.

Our tip: Work with established safari tour operators with an ethical codex who have the local know-how to really assess the situation in the regions they operate in.

The on the ground behaviour is something we have more control over, so here are some basic rules for ethical wildlife practices:

Ethical behaviour in safari parks

- Follow the park rules: This might sound like a no-brainer, but it’s not the reality unfortunately. These rules are in place for a reason and if off road driving is forbidden, let’s just stay on the roads. Even if it means we might miss that cheetah chasing an impala behind the bushes. Each park has a different set of rules, so especially if you’re self driving familiarise yourself with those rules. If you’ve booked a guided safari, then make sure your guide follows the rules. They sometimes prioritise their guests satisfaction and overstep boundaries so you’ll get “the shot” or “check off the Big 5”. Let’s be mindful that we as guests also signal our guides that we have the intention to follow rules and ethical practices and that the animal’s wellbeing actually trumps our own desires.

- Give the wildlife space: Some parks or concessions have rules as to how many cars are allowed at a sighting or how long you’re allowed to stay with an animal during a sighting. If you’re lucky and found the resident female leopard with her new-born cub, watch them for a bit (and from a distance) and then leave them be again.

- Don’t entice animals to come closer to you: No feeding, baiting or other practices should be used that incentivice wildlife to reduce their natural instincts to keep a distance from humans. Why? This kind of behaviour creates human-wildlife-conflicts in the long run. When wild animals learn that they can come closer to humans this usually ends up in casualties (on both sides!). As soon as wild animals come closer to settlements, eat crops (or trash) this ends in disasters and often the animals are being killed as a result. And don’t believe that if an area is fenced that this automatically avoids human-wildlife-conflicts.

- Don’t share geo locations when you post endangered species: Believe it or not, but poachers use Social Media too. They actually scout for rhinos on Instagram through location tags. Usually your guide tells you when it’s ok to share a location and when it isn’t.

Ethical behaviour outside of safari parks

- Zoos: Oh, that’s a complicated one. I would say in general, if you’ve booked a safari, don’t go to the zoo… you’ll not enjoy the zoo anymore once you’ve seen wildlife thrive in their natural environment. But of course that’s a very generic assessment and there’s much more to be said about the topic, yet not necessarily in a safari context. Just know that many parks have been repopulated with animals from zoos as well, so there’s an intricate connection between zoos and safari parks.

- Be very critical when it comes to “wildlife sanctuaries”: We could write a whole separate blogpost on so called “wildlife sanctuaries” and how many actually run foul practices and abuse wildlife for commercial benefits. Judging the ethical practices of a sanctuary can prove daunting. We had some experiences in Myanmar with former working elephants from the logging industry that weren’t easy to digest. Red flags are: Small enclosures, chains around ankles, claims that the wildlife is rescued but then there’s an abundance of cubs and pups (these are usually bred for the baby-loving visitors among us) and if they have any kind of close-up animal encounters on offer.

- Don’t book any “animal encounters”: These include touching, petting, cuddling, hugging, riding, bathing, feeding (with some minor exceptions when you attend feeding sessions where you get to watch trained staff feed rescued animals) or selfie opportunities (Costa Rica has even passed a law that forbids wildlife selfies over a decade ago and now runs campaigns to create awareness how destructive the wildlife selfie culture is).

Generally speaking it’s a very fine line between wildlife actually benefitting from safari tourism up to a tipping point when tourism actually becomes a threat. So it’s always balancing scales here. But being aware and informed is already the first step.

2. Ethical social practices

Now that wildlife is safe & sound, we can take a look at how our safari impacts the people who actually live in the areas we visit. Before I got involved in the safari industry I really didn’t know much about the intricate connections here. Safari tourism started back in colonial times and much of these structures still exist today in a post-colonial world. From fortress conservation practices (as in basically displacing communities and locking them out of fenced-off parks) to community-owned and run lodges and camps – there’s a lot of grey areas in between.

Again this is a very complicated topic and just because a lodge claims to give back to communities, that doesn’t always mean anything. Greenwashing also works in the social department it seems. As an outsider it’s hard to judge if claims are true, so in this regard I would also rely on an experienced safari tour operator to help you put together an itinerary that allows for a socially conscious safari.

Tips for ethical social practices on a safari

- Stay at community-owned lodges & camps: Slowly but surely the industry is changing and residents aren’t merely props to photograph or staff members, but they actually actively participate in the tourism industry. Ask your tour operator specifically for community-owned lodges and camps or research them yourself in preparation for your trip. There’s all-female-run camps in Tanzania, Maasai owned lodges in Kenya and so much more. It’s our responsibility to also create demand for such enterprises.

- Buy souvenirs from local cooperatives: Sometimes even shopping can do good. Trade instead of aid is one of those slogans we’ve heard countless times and this can be put into practice easily on the ground. Don’t shop at the airport or motorway shops, but look for local cooperatives, that are owned and run by the communities. Often lodges and hotels have shops as well, but we would rather suggest to buy directly from the cooperatives, so they can benefit from the direct sale without having to pay any commissions. We always research for cooperatives and then demand stops (especially on travel days between camps) to make time to visit and shop there and maybe even book a tour of the manufacturing facilities.

- Do support reliable local non-profits: There’s different models here. In some concessions or parks you have to pay a fee for their own non-profits for every night you stay on top of the national park fee. In other places there’s a revenue sharing model (Rwanda for example), where the government uses the tourism revenues (park fees) and distributes them to the different districts of the country evenly. This way not only the regions in the North with the exceptional gorilla safaris (and very costly permits) benefit, but also other less-visited areas can participate in the success. If there’s no such mandatory fee we suggest to research local non-profits and donate a percentage of your total trip budget voluntarily.

Tips for ethical photography & local encounters

This is a separate topic which we believe is important to touch, as it’s often a component of a safari: Encounters with tribes to get to know their ways of living and learn about their culture and history. Yet it’s often commercialised these days and feels like a staged photo opportunity more than a cultural exchange.

- Look for authentic local encounters: This is not easy to be honest. Where’s the line between an authentic encounter and a staged photo op in a village? Really, this is hard to judge. When we were in Kenya’s Samburu regions we had very different cultural visits than in the much more commercialised Maasai Mara. Yet, both have their value. In the end it’s down to you and your behaviour during the visit.

- Consent is not consent: So let’s say you’ve booked a Maasai village tour and you’re equipped with your phone or camera looking for great photo opportunities of the colourful beaded women. How to best go about? In standard photography practice consent is the golden standard. So you ask for consent that you can take their photo. Usually this will result in consent (unless you’re getting a NO as an answer, which needs to be respected of course). But even if you’re getting a YES as an answer, be aware there’s a unilateral power play guiding this consent. You’re not two equals doing business with each other, but there’s dependencies. The communities might depend on the revenue generated from the safari tours and posing for photos. You can see this everywhere around the planet, not just on safari of course. People will be dressed in western clothes and only put on their traditional dress to pose for tourists’ photos, etc. – so it’s complicated. So let’s extend consent and make sure the translator knows how the photos will be used. If you have a commercial purpose (as in publishing the photos, making a book, selling prints, etc.), written consent is standard practice by now. And when it comes to children it gets even more delicate!

3. Ecological practices

Now let’s look at the wider impact we create on an ecosystem when visiting as safari tourists. Truly sustainable safaris maybe don’t even exist, but that is probably true for all human life on earth. As soon as we enter this life we create an environmental impact. I don’t want to open Pandora’s box now, but generally speaking we all know that we need systemic change on a global level to reduce our impact. Yet there’s things we can control and without being able to provide an exhaustive list, let’s look at a few ecological practices to consider.

- Leave only footprints: You might know this slogan from your local National Parks, the same of course goes for safaris. In reality this is quite a complicated undertaking as it involves many aspects.

- Waste management: When it comes to waste management it makes sense to inquire with the camps and lodges. Some even offer eco tours of their camps so you can learn how they try to avoid, reuse and recycle waste. What you can do as a guest is to not bring any single use plastics – think water bottles, but also ear swabs (there’s now reusable ones), dental floss (with bamboo instead of plastic), but it even comes down to micro plastics in your beauty products, etc.

- Water management: Waste water is another key element to ecological safaris. Let us give you an example: At Emboo River in Kenya’s Maasai Mara the camp has set up a closed water cycle, that creates zero waste water through an elaborate system of natural water filtration (with plants and microbes). Make sure you use biodegradable products when showering – often eco camps provide these, so you shouldn’t use your own shower gel or hair shampoo.

- What’s on your plate: What you eat on a safari is also something to be considered. And we’re not advocates for only eating “local food” – as in parts of Kenya that would for example mean exclusively eating cattle products such as beef, blood and milk. There’s many camps and lodges with a focus on sustainable food production these days. Many started with herbal gardens, which have grown into full fletched organic vegetable gardens, or they look into reducing food waste by asking guests to pre-order their food. As vegetarians it’s easy for us to speak, but we’ve appreciate that more and more lodges offer plant-based menus as standard and guests have to specifically ask for meat – as opposed to the other way around. This is a step in the right direction and might lead more people to consider going plant-based during their safari. Because livestock, grazing and cattle herding are significant risk factors for wildlife.

- Local transfers: Sometimes it’s impossible to avoid a bush plane to get to the most remote corners (which are often the most beautiful ones on a safari). So this is a complicated one. To avoid unnecessary plane trips try and cram less into your one or two week itinerary. Stay longer in one area instead. Last time we stayed in three different camps in the Maasai Mara and it didn’t get boring – and we could rely on ground transfers in between. When it comes to the safari itself there’s a new trend to rely on fully solar powered electric vehicles, which can also help reduce the carbon footprint.

Again this list is not exhaustive, so please do leave a comment if we missed something essential!

What’s left? Should we even go on safari?

One remark we sometimes get is if going on a safari is ethically justifiable at all these days. Our answer to this is – as always – that there’s no black and white, but many shades of grey. A safari can be a means for conservation as well as an exploitative undertaking. But let’s look at why safari tourism can be a force for good:

Only 4% of mammals on our planet are wild animals.

The rest is livestock (62%) and humans (34%). So the literal SPACE on our planet that is left for wild animals is under serious threat and pressure. Often it comes down to what’s called “choices of land use”. I’m sure not all of you have heard about this term, because many of us still have a romanticised idea about our planet and how wild it is, but in reality we as humans have encroached into most of the wild spaces on Earth.

Creating a national park or wildlife refuge is a choice of land use. The alternative would usually be agricultural use (plantations, cattle grazing) or the development of human settlements. In Kenya wildlife corridors are still turned into cattle farms or rose plantations. Given these are the realities of life on our planet we believe dedicating space to wildlife and natural ecosystems is reason enough to validate safari tourism.

Yet, these ecosystems need to be managed, otherwise they wouldn’t withstand human interference and encroachment. Parks need law enforcement for community safety and against poaching, scientific ecosystem monitoring, wildlife management and so much more. And this costs money. In return there needs to be a sustainable source of revenue and this is where tourism comes into play – when done right.

The most important part is to create awareness on responsible tourism practices as a first step. Once we as travellers are aware that our choices undeniably create an impact, we can take it from there.

Help share this post: